It now seems like a tradition; every time “Barber” gets on the music stand, a discussion arises about what sistro, sistri and sistrum mean and what instruments correspond to that nomenclature. I´ll try to clarify this issue, and I´ll begin with a little bit of History.

The Ottoman Empire started as one of the many Turk states in Asia Minor (Anatolia) and ended up as a military, commercial, cultural, political and territorial power spread over three continents: Asia (Anatolia, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Iran, part of the Arabian Peninsula…), Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Soudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea…) and Europe (Greece, Bulgaria, Rumania, Moldavia, Russia, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia…). It extended in time between the 13th and the 20th century and got to its peak in the 1500s and 1600s.

The Sultan created an elite infantry corps which also served as his praetorian [hand-picked elite-Ed.] guard: the janissaries (yeni çeri –“new soldier” originally two words). From them, and because of paronomasia [use of a word in different senses or the use of words similar in sound-Ed.], comes the term “jingle Johnny”. Janissaries were accompanied by military bands named mehteran (mehter being a musician in the mehteran). These bands compromised different wind instruments (which we don´t care for… 😃) and percussion ones (which we do care for… 😃 ). So, a mehteran featured these percussion instruments: kos (a big bowl shaped drum carried on horses, camels or elefants and beaten with two sticks), tabilbaz (a slightly smaller bowl shaped drum, also carried on horse and beaten with just one stick. From the word “tabil” come the Spanish words tabal, atabal, timbal…), davul (a fairly big double head rope drum, hit with a mallet on one side and a thin rod on the other), nakkare (two small bowl shaped drums), zil (cymbals) and cevgen (Turkish crescent). Some authors claim that dafs and some other kind of frame drums were part of the percussion forces of the mehteran, but iconography doesn´t prove this (we also know how intimately frame drums were connected to female deities, priestesses, bacchants [drunken reveler – Ed.] and women in general). Please note that the triangle was not part of the mehteran: it was already known in Europe, as it is mentioned in a 10th-century manuscript (this is important and will be commented soon). Mehteran are considered the first military bands in History, and they were used to march, transmit orders, intimidate the enemy, entertain the Sultan…

Because of the expansionist policy of the Ottoman Empire, we, Europeans, got to know their army and, thus, their mehterans. The Sultan donated such a band to King August II of Poland (he died in 1733). Anna of Russia adopted one in 1725 and Austria saw one parading in Vienna in 1741. But, in all cases, these bands were not exactly mehterans, but a “stylized copy” built mainly around the percussion instruments, and because they weren´t an exact replica, but more and idealized recreation of what the exotic Orient may be to Europeans, “indigenous” instruments, like the triangle, were included (the one we mentioned above that was not part of the “authentic” mehteran). These bands caused a great impression, and they soon became something fashionable, influencing Western composers. Sonatas “alla turca”, operas with oriental flavour, marches and military music… Turkish music was in vogue, and even pianofortes had an alla turca pedal which activated several percussion instruments. Even Turkish clothes, hairstyles, coffee… were trendy.

It didn´t take long for this “percussion section” to get into the orchestra. We have examples by Gluck in 1759, but let´s move on to Italy, where the interest of this article is focused on… In this country, the percussion section (apart from the timpani already present) compromised bass drum (almost still a davul, with two different beaters and techniques for both heads. There´s a famous cartoon featuring “Tamburossini” playing one of them making laughs of his profuse use of the Turkish percussion), cymbals, triangle (an “autochthonous” instrument”), Turkish crescent, snare drum… This group of instruments was named Banda Turca or Bassa Música, and the earliest example it can be found in is in L´amante prigionero (C. Bigatti-1809). From then on, the presence of the Banda Turca is obiquitous in Italian theatres during the 19th century. Of course, it can also be found in Rosinni´s Il barbiere di Seviglia, La gazza ladra, Tancredi, L´italiana in Algeri, Otello…

The availability of the Banda Turca would have depended on the importance of the theatre. Important ones would have had a full section, while small regional ones may only have had a timpanist. This is important, because it dictated how music was written for the Banda Turca. That, together with the improvisatory character of the Bassa Musica, made composers just indicate where the Banda was required, and it was the task of conductors, assistants, concert masters or editors write the parts according to the percussive forces available at the theatre the work was going to be performed in (thus the many different original manuscripts available, or even the presence of several different writings/calligraphies in the same manuscript -which indicates different people wrote on the score-). This was also the case with the banda sul palco or banda sulla scena (“onstage band”), where a piano reduction was used, and the task or orchestrating it according to the instruments available at the theatre was that of the conductor, assistant, pianist, editor…

We just have to see manuscripts from Rosinni to realize he just doodled some “spaghetti lines” in the Banda Turca staff, letting others write and arrange the parts. Verdi himself specified in the manuscript of Luisa Miller that “conductors should not add the bass drum in this entire opera, not even in the overture”. This proves that, apart from the works where the Banda Turca was specifically requested, it was also used ad libitum, requested or not, to reinforce forte and dramatic passages and the introductions and finales.

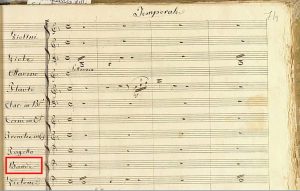

Knowing this, it is now funny to realize that, in modern performances, the storm in Il Barbiere goes by with no percussion at all but, if we have a look at one of the manuscripts, we can see there´s a staff in the score indicating Banda. As usual, it goes completely empty for the whole number (as it was common practice at that time, as we have just seen), as it was the task of others to arrange and write the part. In Rosinni´s time that storm would have been played with a full Banda Turca to a great effect (what better than percussion to sonically imitate a storm?) but, nowadays, the storm is nothing but a light breeze because the absence of percussion due to editors, conductors and musicians not knowing historical practice.

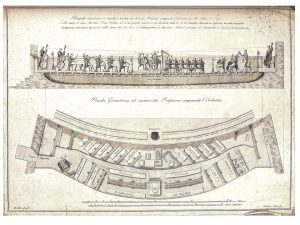

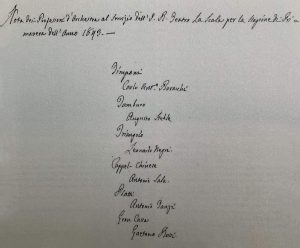

Now, it is important to note that, even in the Banda Turca, there was a “subsection” compromising the ringing metallic instruments (cymbals, triangle and jingle Johnny) named sistri. With regard to the jingle Johnny, we have to say it was always (ALWAYS!) played together with bass drum and cymbals. Although no specific part was written for it (see the compositional/arranging practice commented above), it was without saying that it was to be played together with cassa and piatti. We positively know the jingle Johnny was part of the Banda Turca (and it was used with profusion) thanks to payrolls, poster bills, hand bills, letters, records… The only time we can find a written part for jingle Johnny is in Ferdinando Paer´s L´eroismo in amore. Because it was always played paired with the bass drum and the cymbals, its presence was always taken for granted when a part for these instruments was written. The picture below is a note stating the members of the percussion section at La Scala in the 1843 season. It proves the presence of the jingle Johnny (and how bass drum and cymbals were played separately by two players, but that´s a different story…).

We now have all the ingredients to clarify what sistro and sistri mean. Let´s go for it…

There are there three terms used in 19th-century Italy for “triangle”: triangolo, acciarino and sistro. Triangolo presents no problem whatsoever, so let´s skip it. Acciarino (from acciaio -“steel”- and the diminutive -ino) is used more frequently in Southern Italy, and it can be found, for instance, in Bellini´s I Puritani and I Capuletti e i Montecchi.

Sistro (ending with an “o” indicates it´s singular) is a term only to be found in Northern Italy. It also means “triangle”, and proof can be found in page 145 of Melchiore Balbi´s Grammatica ragionata della música considerata sotto l´aspetto di lingua (“A reasoned music grammar considered under language aspects”): “The sistro is a steel sheet bent in the form of an equilateral triangle”.

Triangolo, acciarino and sistro may have been ringed or not also depending on where on the Italian peninsula the term may have been used. According to page 235 of Domenico Gatti´s Gran trattato d´instrumentazione storico-teorico-prattico per la banda (“Grand historical-theoretical-practical treatise on instrumentation for the band”), the addition of metal rings to the base of the triangle was a lasting tradition in Southern Italy. So, because acciarino was a Southern term, it may have been, in all probability, ringed. The sistro, because a Northern term, may have been, in all probability, unringed. The triangolo may have been ringed or not depending on where in Italy the term was used.

By now, it should be very clear what sistro means: “triangle” and nothing more than “triangle”. Let´s go on now with sistri.

Sistri, ending with an “-i”, is the plural of sistro, thus “triangles”. Could it be that whoever arranged the percussion parts (we know Rossini didn´t) was prescribing the use of more than one triangle played by more than one player? According to page 291 of James Blades´ “Percussion instruments and their history”, François-Adrien Boïeldieu scored for two triangles (high and low) in his opera Le calife de Bagdad. Also, in his book (page 204, footnote 1), Blades cunningly states that “Rossini may have had the triangle in mind (now generally used)”. We also know that percussionists in that period were regularly recruited from military bands, and doubling instruments was common practice in that context. So… Is sistri an indication for more than one triangle being played by more than one player? Well… Taking into account that Boïeldieu was French (Rossini was Italian), that just one example like Le calife can be found in the whole repertoire, that even important theatres show no records, payrolls, handbills, poster bills or letters demonstrating that more than one player was used to play various triangles at the same time, we have to opt for the easy, logical answer: sistri doesn´t indicate the use of more than one triangle.

What does, then, sistri mean? As stated before, the sistri are the ringing metallic instruments (instruments, because it´s plural) in the banda turca that could be added depending on the percussion forces available at the theatre the music was going to be played in (cymbals, triangle, jingle Johnny). Their addition would have depended on the inventory of the theatre and the arrangement by the conductor, assistant… In Giuseppe Persiani´s Ines de Castro, the staff for the sistri, at one point, shows the indication triangolo, so as to isolate this instrument from the rest of the sistri, requesting the latter to tacet. With this indication, it is demonstrated that sistri (in plural) are differentiated from the triangle, so sistri doesn´t mean “more than one triangle”. Carlo Pepoli, around 1830, also makes a distinction between sistri and triangles. So, sistri are the ringing, noisy metallic instruments that could be added to the banda turca at the discretion of the arranger and, depending on their availability, at any particular theatre.

What is a sistrum? Sistrum is nothing but Latin. Sistrum is second declination, nominative case, singular number, neutral gender. Latin was seen as a prestigious, cultured language, and whoever arranged the part (we know Rossini didn´t), considered sistrum more refined than sistro (that´s what sistrum means, thus “triangle”) and used the Latin term.

People tend to identify the term sistrum with the Egyptian hand percussion instrument connected to the cult of Isis. That´s because they ignore the term sistro and its “Latinised” version. There´s no single work (no one!) in the whole repertoire in 19th-century Italy asking for sistrum in the sense of the Egyptian hand shaker. Was Rossini a “rara avis” who decided to orchestrate for an instrument no other single composer wrote for and no other single part exists? First thing: we know, as it was common practice at that time, that Rossini didn´t orchestrate asking for it (in the sense we understand it today), as he doodled some instructions and someone else arranged the part. Second thing: wouldn´t any other composer have scored for such an instrument, like they scored for other common percussion instruments? Let´s try and find the easiest, logical, common sensed answer to this question… Did Rossini (and his arrangers) ask for a ubiquitous instrument, known to every single composer and percussionist, part of a well stablished banda turca, for which records exist and its nomenclature, although variable depending on the region, was well known and is perfectly documented? Or, did Rosinni (and his arrangers) ask for an instrument that can be found in no single theatre, no other single part can be found and is not featured in any other work for a whole century in a whole country? Well… I know where the easy, logical answer is.

Others claim sistro refers to an instrument known as sistro armónico, sistro a campanelli, sistro a suoni intonati, scampanaio, campanelli armonici… These instruments do have existed, and consist of a series of tuned small bells or plates (think glockenspiel). The problem is that the first record of this instrument is the opera Saffo by Paccini, premiered in 1840 at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. Il barbiere di Seviglia was premiered in 1816, so it´s hard to accept this kind of sistro was used 24 years before the first recorded used of the sistro armonico.

Again, let´s try and find the easiest, logical, common sensed answer to this question… Did Rossini (and his arrangers) ask for a ubiquitous instrument, known to every single composer and percussionist, part of a well stablished banda turca, for which records exist and its nomenclature, although variable depending on the region, was well known and is perfectly documented? Or, did Rosinni (and his arrangers) ask for an instrument that was not used until 24 years later and records show it was very scarcely used from 1840 on? Well… I know where the easy, logical answer is.

Some claim that different pitches are asked for… We have to remember that those indications are not by Rossini, but by the arranger/editor. Sometimes, bass clef is used for the cassa and treble clef for the sistri (like in the spartitino for the end of the first act in “Barber” found in the manuscript). When different “pitches” are notated no clef can be found, so we really can´t affirm different pitches are requested. It can be simple untidiness by the copyist or alternation between sistri. Stems up/stems down have been used but, to me, this simply indicates that, whoever wrote that, knew his stuff and was writing a technique every single triangle player in the world knows and applies when rolling or playing fast passages: the alternate striking of the side and the base of the triangle. This is also linked to the text of the music happening at that very moment: Alternando questo e quello, pesantissimo martello (“alternating this and that, oh heavy hammer”). Also, the choir part sings Mi par d´esser con la testa in un´orrida fucina (“it seems like my head is inside a horrendous forge”).

It is quite clear to me that the instrument Rossini had in mind was the humble and simple triangle, but we, as percussionists, tend to like using exotic and uncommon instruments, and we never miss a chance to use them but, I´m afraid, the solution is way more simple and unexotic than we would like it to be.

So, the instrument we all rave about when we get Il barbiere on the music stand, is the triangle. Sorry about that! [Not-Ed.]😃

Sources:

“Studi Verdiani”, vol. 11

“The timpani and percussion instruments in 19th century Italy” (Renato Meucci)

“Percussion instruments and their history” (James Blades)

“Rediscovering and reconstructing the sistrum in Rossini´s The Barber of Seville” (Simone Fermani)

Imslp.org

Wikipedia

David Valdés started playing piano at the age of seven. He discovered percussion at sixteen and studied both instrumental disciplines for several years but, once he gained his Bmus in Piano, percussion became his main interest.

He got his Bmus in Percussion at the Oviedo Conservatory of Music under Rafael Casanova (OSPA), obtaining the highest marks (“Angel Muñiz Toca” Extraordinary Award and “Final Degree” Award). He also gained a Bmus in Solfege, Sight Reading and Transposition. He also has been trained in Chamber Music, Music Theory and Counterpoint.

David attended the Madrid based “Centro de Estudios Neopercusión”, where he studied with Juanjo Guillem (ONE), Enric Llopis (ORTVE), Francisco Diaz (OST), Juanjo Rubio (OCM), Oscar Benet (OCM), Belen López, David Mayoral and Serguei Sapricheff.

He studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London with Andrew Barclay (LPO), Simon Carrington (LPO), Leigh Howard Stevens, Nicholas Cole (RPO), Dave Hassell, Paul Clarvis, Neil Percy (LSO) and Kurt Hans Goedicke (LSO), where he gained his Postgraduate Diploma in Performance (Timpani and Percussion) and his LRAM. He also studied Jazz with Trevor Tompkins, Orchestral Conducting with Denise Ham and Choral Conducting with Patrick Russill.

David has attended many courses and master classes by renowned musicians: Jeff Prentice, Rainer Seegers, Benoit Cambrelaing, David Searcy, Ben Hoffnung, Philippe Spiecer, Enmanuel Sejourné, Keiko Abe, Eric Sammut, She-e Wu, Joe Locke, Anthony Kerr, Dave Jackson, Makoto Aruga, Chris Lamb, Collin Curie, Evelyn Glennie, Mircea Anderleanu, Steven Shick, John Bergamo, Airto Moreira, Birger Sulsbruck, Peter Erskine, Dave Weckl, Bill Cobham, Carlos Carli, George Hurst, Arturo Tamayo, Collin Meters, José María Benavente, Román Alís, Fernando Puchol, Michel Martín, Javier Cámara, Francisco José Cuadrado… These musicians have trained him in Percussion, Piano, Contemporary and Modal Harmony, Jazz, Conducting, Music Production, Editing and Microphone Techniques.

He was awarded the “Principality of Asturias Government Scholarship” three times in a row, he was finalist at the “International Keyboard Percussion Competition” sponsored by the “Yamaha Foundation of Europe” and was runner-up for the “Deutsche Bank Pyramid Awards”, given to innovative performance and composition projects.

David has played with the following orchestras: Gijón Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Principality of Asturias Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Oviedo Filarmonía (Spain), Asturias Classical Orchestra (Spain), Spanish National Orchestra (Spain), Catalonian Chamber Orchestra (Spain), Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Orchestra of the University of Oviedo (Spain), City of Avilés Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Moscow Virtuosi (Russia), Concerto München Sinfonieorchester (Germany), WDR Rundfunkorchester Köln (Germany), Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic Orchestra (Poland), Orquestra do Norte (Portugal) and the Ulster Orchestra (UK). He has also played with early music ensembles (Forma Antiqva, Memoria de los Sentidos, Sphera Antiqva and Ensemble Matheus), and chamber groups (RAM Percussion Group, Neopercusión and Ars Mundi Ensemble).

He has translated into Spanish “Method of Movement for Marimba” (L. H. Stevens), the internationally acclaimed book used in conservatoires and universities worldwide. He is, also, the Spanish translator of www.percorch.com, website used by many orchestras to organize their percussion sections.

He has taught at the Gijón and Oviedo Conservatories of Music. His discography includes many different genres, and he has worked as a session musician, arranger and on-line instrumentalist as the result of his interest in recording, sound and technology. David is a busy timpani/percussion freelancer and runs his own business: “Producciones Kapellmaister”.

David Valdés enjoys sailing, windsurfing, snowboarding, rollerblading, reading, and playing with his two daugthers: Carmen and María.

A very good article ! But I should point out that the earliest use of “sistro” for a tuned metallophone is by G.B. Ariosto in 1682 : “Il Sistro, nomato il Timpano.”