by David Valdés

TAMBOURINE PART IN “POLOVTSIAN DANCES”: AUTHORSHIP, NOTATION AND TECHNIQUE

(PART ONE)

“Polovtsian Dances”, by Alexander Borodin, is a suite from his opera “Prince Igor”, a work that remained unfinished when the composer died in 1887.

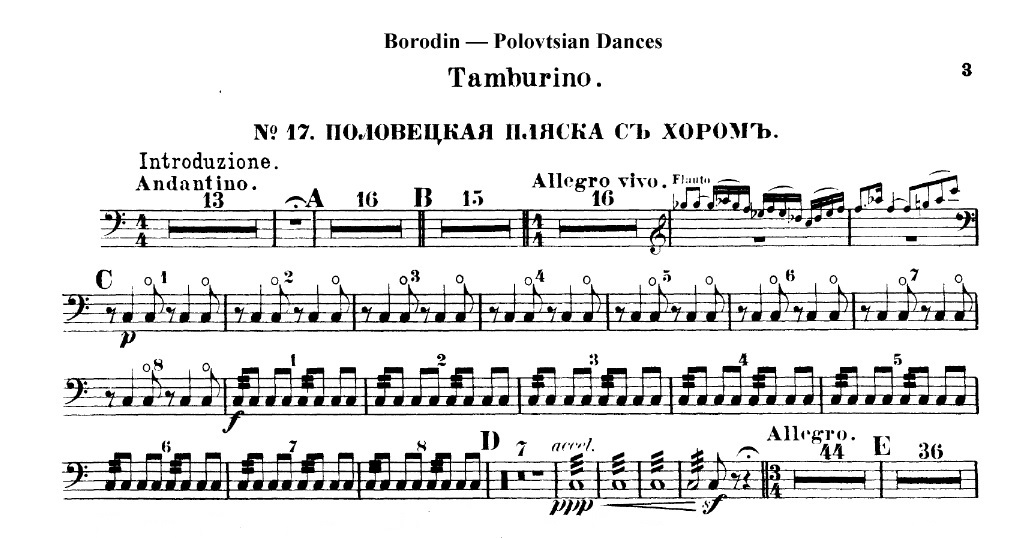

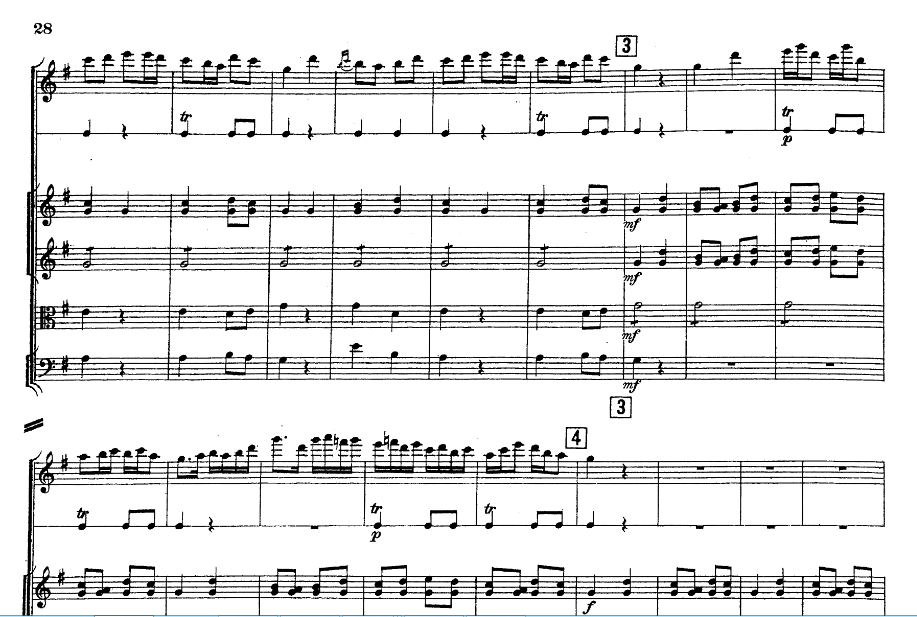

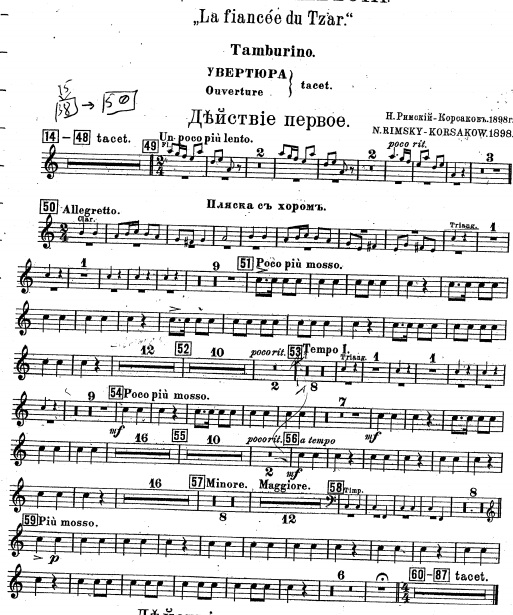

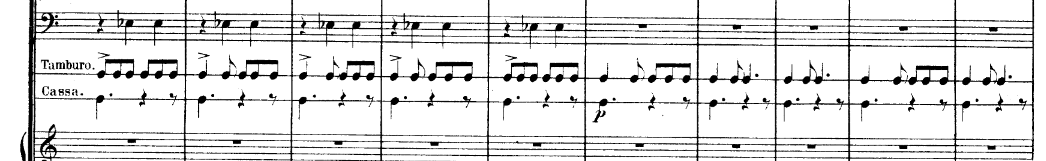

Dances #8 and #17 (taken from the second act) feature an unusual notation for the tambourine:

Before going on, it should be noted that, in Dance #17, there is a misprint in the part: the circles should be above the crotchets (quarter notes-ed), not above the quavers (eighth notes-ed). The score confirms this point:

This notation uses a stems up/down nomenclature together with circles above certain notes. What does it mean? What kind of two different strokes does it indicate? Patience… Before we try to shed light into this matter, there is another important issue we should clarify in the first place: who wrote the tambourine part for “Polovtsian Dances”? We have some first-hand information from those involved in the process of completing “Prince Igor” but, sadly, it is quite contradictory… Rimsky-Korsakov gives us some clues in his “Chronicle of My Musical Life” (1909):

“There was no end of waiting for the orchestration of the Polovtsian Dances, and yet they had been announced and rehearsed by me with the chorus. It was high time to copy out the parts. In despair I heaped reproaches on Borodin. He, too, was none too happy. At last, giving up all hope, I offered to help him with the orchestration. Thereupon he came to my house in the evening, bringing with him the hardly touched score of the Polovtsian Dances; and the three of us—he, Anatoly Lyadov, and I – took it apart and began to score it in hot haste. To gain time, we wrote in pencil and not in ink. Thus we sat at work until late at night. The finished sheets of the score Borodin covered with liquid gelatine, to keep our pencil marks intact; and in order to have the sheets dry the sooner, he hung them out like washing on lines in my study. Thus the number was ready and passed on to the copyist. The orchestration of the closing chorus I did almost single-handed …”

If we are to trust Korsakov´s words, the “Polovtsian Dances” were orchestrated by three people: Korsakov himself, Lyadov and Borodin (while still alive, quite obviously). Sadly, Korsakov´s memories do not seem to be accurate, as in the same book he also states the following:

“Glazunov and I together sorted all the manuscripts … In the first place there was the unfinished Prince Igor. Certain numbers of the opera, such as the first chorus, the dance of the Polovtsy, Yaroslavna’s Lament, the recitative and song of Vladimir Galitsky, Konchak’s aria, the arias of Konchakovna and Prince Vladimir Igorevich, as well as the closing chorus, had been finished and orchestrated by the composer. Much else existed in the form of finished piano sketches; all the rest was in fragmentary rough draft only, while a good deal simply did not exist. For Acts II and III (in the camp of the Polovtsy) there was no adequate libretto – no scenario, even – there were only scattered verses and musical sketches or finished numbers that showed no connection between them. The synopsis of these acts I knew full well from talks and discussions with Borodin, although in his projects he had been changing a great deal, striking things out and putting them back again. The smallest bulk of composed music proved to be in Act III. Glazunov and I settled the matter as follows between us: He was to fill in all the gaps in Act III and write down from memory the Overture played so often by the composer, while I was to orchestrate, finish composing, and systematize all the rest that had been left unfinished and unorchestrated by Borodin”.

In the paragraph above he seems to contradict himself, as Korsakov attributes the orchestration of the “Polovtsian Dances” to the composer (Borodin, already dead), forgetting that, in the first paragraph, that task is attributed to three people (Borodin -still alive at that time-, Korsakov and Lyadov). He also contradicts himself stating the following in the first paragraph: “The orchestration of the closing chorus I did almost single-handed” (Korsakov), while in the second paragraph he states “…as well as the closing chorus, had been finished and orchestrated by the composer” (Borodin). Very contradictory and confusing if you ask me. Sadly, our first-hand source (Korsakov) does not seem to be reliable.

This is not the only unreliable information in Korsakov´s book, as Glazunov scoring the overture from memory is a myth. In his own words (“Memoir”, 1891, published in Russkaya muzikalnaya gazeta, 1896), Glazunov states the following:

“The overture was composed by me roughly according to Borodin’s plan. I took the themes from the corresponding numbers of the opera and was fortunate enough to find the canonic ending of the second subject among the composer’s sketches. I slightly altered the fanfares for the overture … The bass progression in the middle I found noted down on a scrap of paper, and the combination of the two themes (Igor’s aria and a phrase from the trio) was also discovered among the composer’s papers. A few bars at the very end were composed by me”.

So, even the original and direct source (Rimsky-Korsakov) is confusing: he does not clarify who wrote this interesting tambourine part (and Glazunov disproves certain Korsakov´s claims). Since we cannot trust Korsakov´s memories, a research work is required to find out who wrote the tambourine part in the “Polovtsian Dances” and, therefore, what its nomenclature means.

I have checked all the works by the composers mentioned (Borodin, Lyadov, Rimsky-Korsakov and Glazunov. Stasov, mentioned together with Korsakov as those who recovered the musical material from Borodin´s house once dead, is irrelevant in the equation, as he was a critic, not a composer). They, to a greater or lesser extent, messed around with the score and completed it. Studying how they wrote for tambourine may clarify things up.

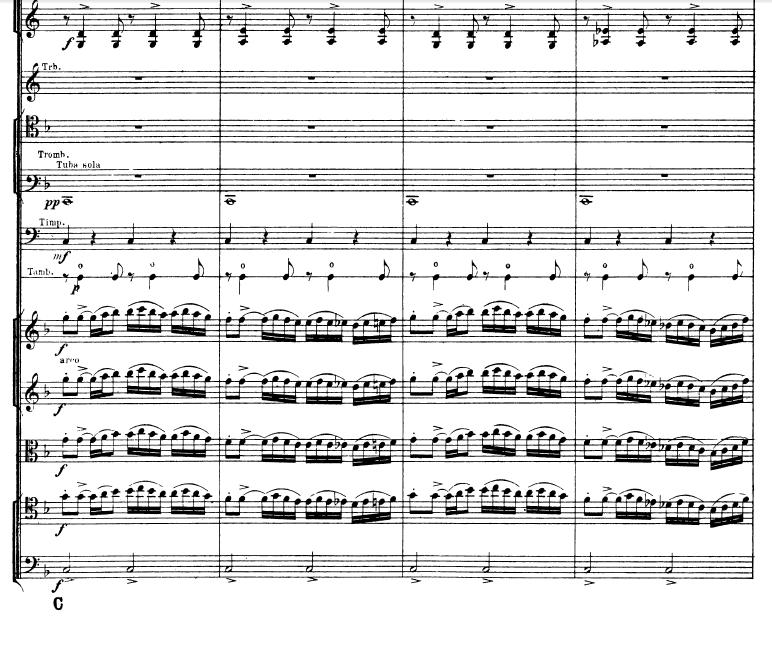

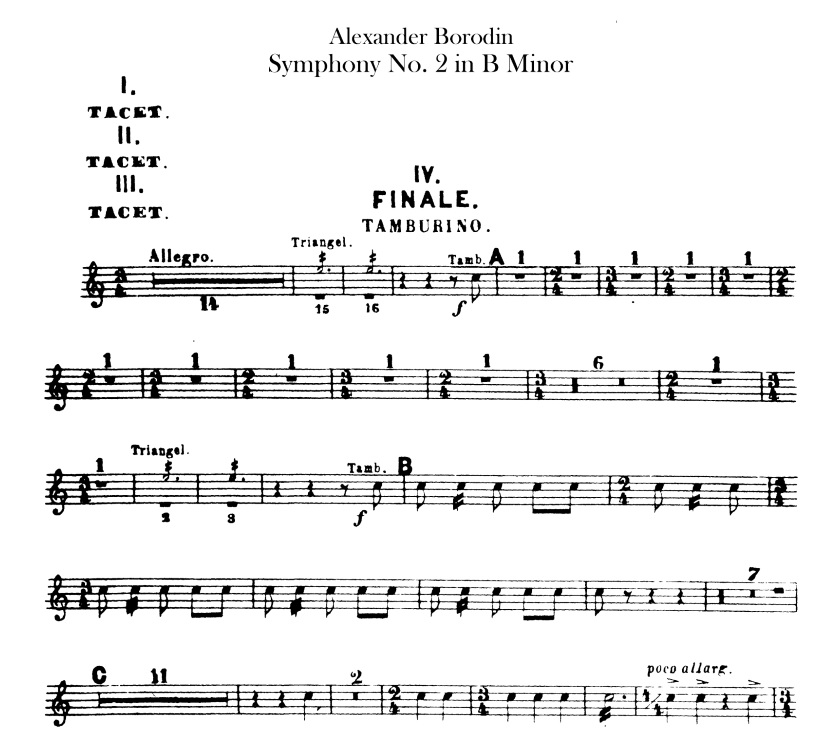

Let us start, then, with the original composer: Borodin. What other works did Borodin write featuring the tambourine? I have checked all of Borodin works (which are not many, as he enjoyed a happy and prosperous life as a chemist), and his Symphony #2 is the only one in which tambourine is asked for. His “Petite Suite” for piano, orchestrated by Glazunov, does feature a tambourine part, but it is obviously not by Borodin´s hand.

The tambourine part in Borodin´s symphony #2, although nice to play, does not resemble the tambourine part of “Polovtsian Dances” very much:

Did Borodin write the tambourine part of the “Polovtsian Dances”? I do not think so… The tambourine part in the “Polovtsians Dances” we know nowadays does not resemble at all the writing of the only work in which Borodin scored for tambourine. Could Borodin have written such a colourful part in the “Polovtsian Dances” while having ignored the tambourine (and this particular technique/writing) in all of his other works? Well… Could be, but I am inclined to think that, according to the very simple writing for tambourine in his Symphony #2, the intricate and colourful part in the “Polovtsian Dances” was written by someone else.

Let us now check the works by Lyadov, another “suspect”. He wrote many piano works, but his only orchestral pieces where the tambourine is present are the following: “Five Russian Folk Songs” (the tambourine is featured in dance #2), “Eight Russian Folk Songs”, op. 58 (the tambourine is featured in dances 7 and 8), “Pro Slarinu”, op. 21b (which features an interesting 5/4) and “Mazurka”, op. 19. There is nothing in his writing for tambourine that resembles in any way the tambourine part of the “Polovtsian Dances”. Could Lyadov have scored the “Polovtsian Dances” using a notation and a tambourine technique he did not use in his own works? Well… Could be, but I do not find that option plausible. You do not keep a specific technique/notation so you can use it to complete a work by a dead colleague while refraining from using it in your own works…

“Five Russian Songs” (#2). Very simple and standard tambourine writing.

“Eight Russian Folk Songs, op. 58” (#7). Again, no special writing for tambourine.

“Eight Russian Folk Songs, op. 58” (#8). Very standard tambourine writing.

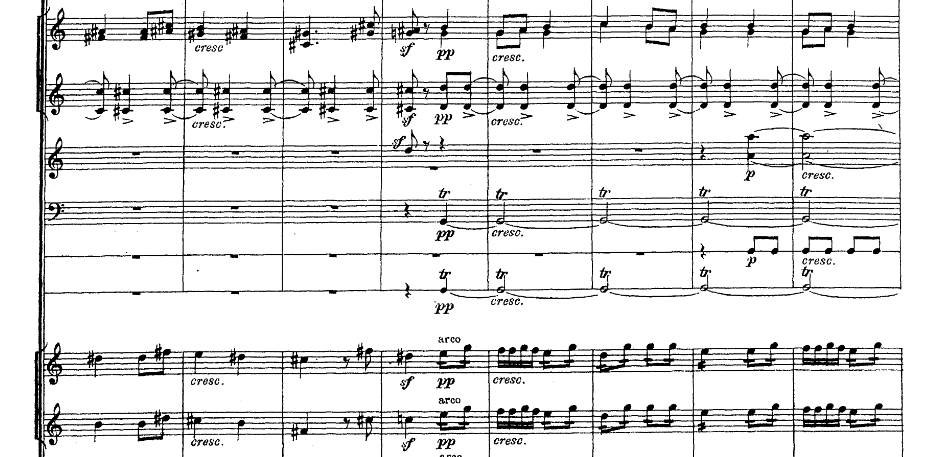

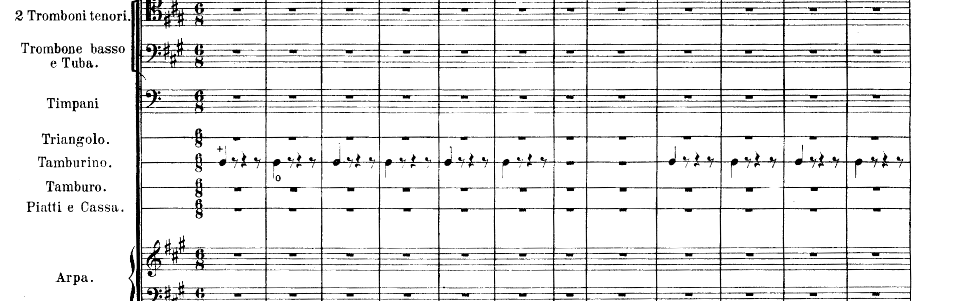

Let us now check all of Rimsky-Korsakov´s works. He wrote for tambourine in “Fantasy on Serbian Themes”, “Symphony #2“, “Overture on Russian Themes”, “Capriccio Spagnol”, “Scheherezade”, “Mlada”, “Le Coq d´Or”, “Fantasie”, “The Invisible City of Kitseh”, “A Night on Mountain Triglav” (extracted from “Mlada”), “The Tzar´s Bride” and “The Snow Maiden”. We know Rimsky as one of the greatest orchestrators, and his tambourine parts are musical, imaginative, very well written, idiomatic and always a challenge, but we can find nothing in Korsakov´s tambourine writing resembling the tambourine style of the “Polovtsian Dances” (or even the peculiar notation found in the latter). Being such a great orchestrator, is it possible that Rimsky-Korsakov used a particular notation/technique for the tambourine only when completing a work of a dead colleague, but did not use it in his own works? Not very plausible if you ask me…

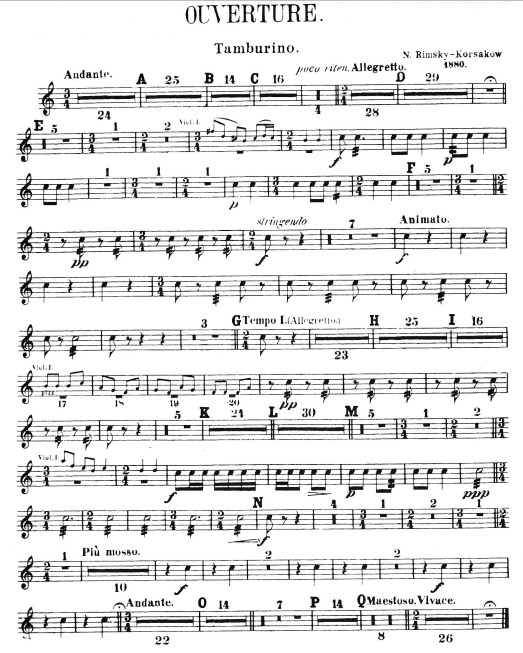

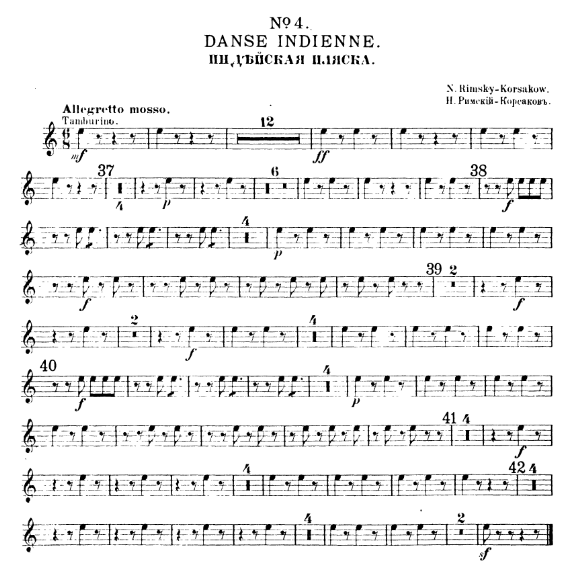

“Fantasy on Serbian Themes”. Very simple writing for tambourine.

”Symphony #2”. An interesting part, but nothing close to the “Polovtsain Dances”.

”Symphony #2”. An interesting part, but nothing close to the “Polovtsain Dances”.

“Overture on Russian Themes”.

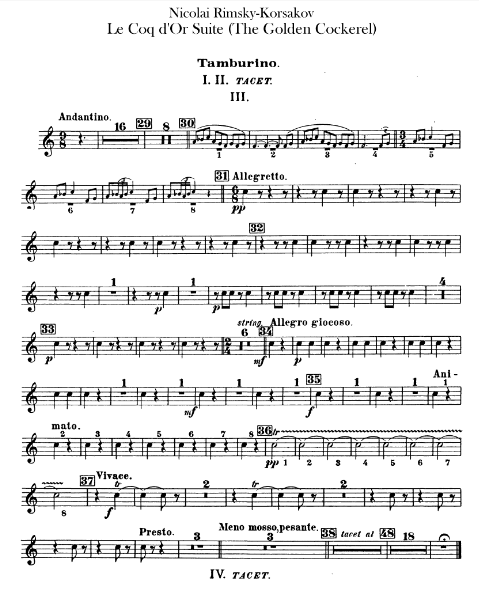

“Mlada”

“Le Coq d´Or”

“A Night on Mountain Triglav”

“The Tzar´s Bride”

“The Snow Maiden”

We know “Capriccio Espagnol” and “Scheherezade” very well, and nothing can be found on them resembling the writing in the “Polovtsian Dances”.

Let us now check all the works by Glazunov, who scored for tambourine in “Carnaval”, “Chopiania”, “Cortège Solennel” op. 50, “Scène Dansante”, op. 81, “Introduction et la Dance de Salomée”, “The Kremlin”, “Overture #2”, “Paraphrase on the Hymn of the Allies”, “Raymonda”, “Ruses d´Amour”, “Scenes de Ballet”, “The Seasons”, “Serenade #1”, “Suite Caractéristique”, “Un Fête Slave” and “Rhapsodie Orientale”. I have checked all his orchestral works and I can confirm how new, fresh, clever, brilliant and flashy his writing for tambourine is. I think we should start giving this composer and his tambourine parts the credit and importance they deserve.

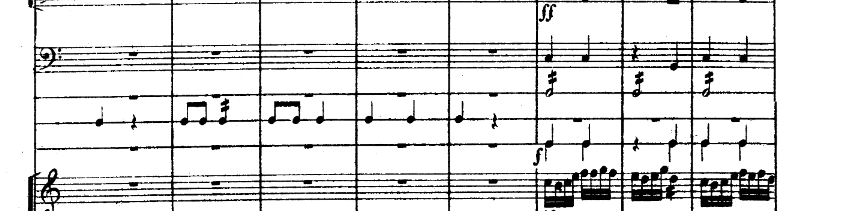

These are the orchestral works written by Glazunov in the 1887-1890 period (death of Borodin and completion and premiere of “Prince Igor”): “La Fôret”, “Mazurka for Orchestra”, “La mer”, “Two Pieces for Cello and Orchestra” and “Wedding March” feature no tambourine part. “The Kremlin”, “Un Fête Slave” and “Rhapsodie Orientale” do feature a tambourine part. “The Kremlin” and “Un Fête Slave” present no special notation/techniques. “Rhapsodie Orientale” does…

“Rhapsodie Orientale”, op. 29 was composed in 1889 (and published in 1890, when “Prince Igor” was premiered), so the completion of “Prince Igor” and the composition of “Rhapsodie Orientale” occupy the exact same time frame. This means Glazunov may have worked at the same time on both “Prince Igor” and “Rhapsodie Orientale”.

“Rhasodie Orientale” is deeply influenced by “Scheherezade” (Rimsky-Korsakov). “Scheherezade” was completed in the summer of 1888 while Korsakov was working on “Prince Igor” (see the parallelism?), and “Rhapsodie Orientale” was completed in 1889 while Glazunov was working, too, on “Prince Igor”. Glazunov was a student of Rimsky-Korsakov, they became close friends and were part of what was got to be known as the “Belyayev circle”, a group of musicians around Mitrofan Belyayev (a rich merchant and music philanthropist and publisher) which included Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, Lyadov, Stasov, Ossovsky, Maliszewsky… Some of these names should already sound familiar to you.

They were interested in orientalism and made intense use of the whole tone scale, leading to a “fantastic style”. It is no coincidence that, after Rimsky-Korsakov wrote his “Scheherezade”, his pupil, friend and member of the Belyayev circle, Glazunov, tried his own orientalist orchestral work. The similarities between both works (“Scheherezade” and “Rhapsodie Orientale”) are evident: superposition of binary and ternary rhythms, dotted rhythms, harmony (whole tone scale), orchestration…

We have here a perfect parallelism: Rimsky-Korsakov writing an exotic and orientalist orchestral work while completing Borodin´s “Prince Igor” while, influenced by his former teacher, Glazunov writes his own exotic and orientalist orchestral work one year later while completing Borodin´s “Prince Igor”. All this happening during the exact same time frame: 1887 (death of Borodin)-1890 (premiere of “Prince Igor”). In between, both composers wrote their own “oriental stravaganza” and completed Borodin´s opera.

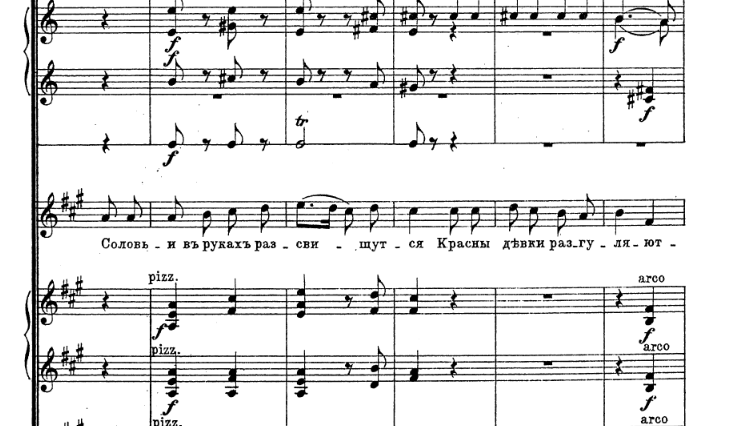

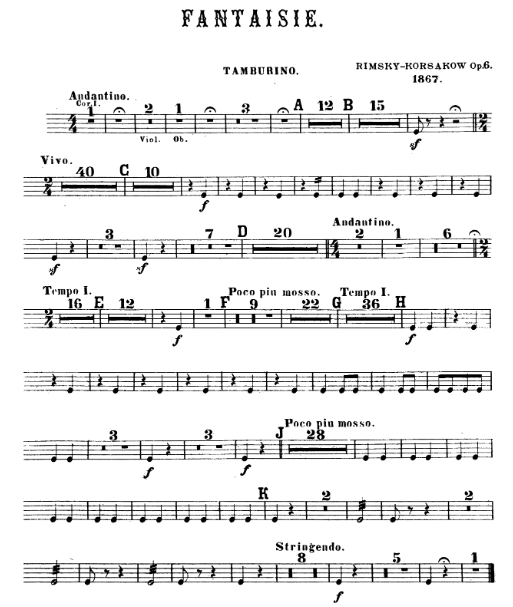

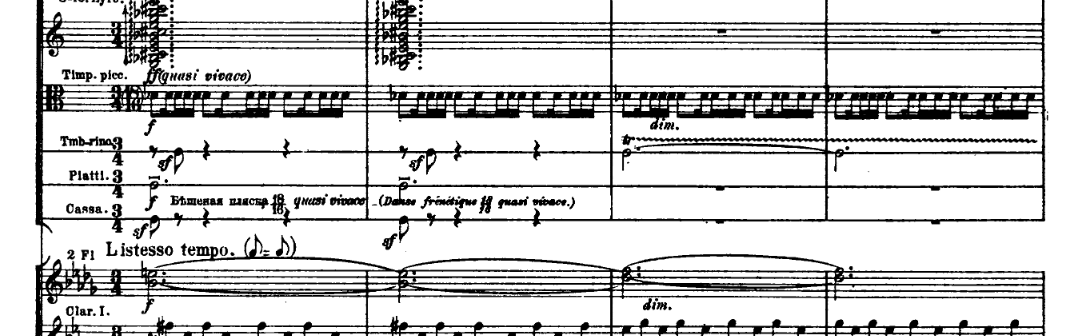

Why is “Rhapsodie Orientale” important? Because it is quite obvious that Glazunov, working at the same time on both the “Rhapsodie Orientale” and the “Polovtsian Dances”, used the same tambourine technique and writing in both works. This is number II of “Rhapsodie Orientale” and, as you can see, it features exactly the same writing for tambourine as in the “Polovtsian Dances”:

This second number is titled “Dance de Jeunes Gens et des Jeunes Filles” (“Dance of the Young Men and the Young Girls”). Dance #8 in “Polovtsian Dances” is titled “Пляска половецких девушек” (“Dance of the Polovtsian Maidens”). We have a common denominator here: dancing young people.

But, this is not the only thing they have in common: both dances are in 6/8, the tempo is presto “in one” (terribly fast) and both feature the same notation in the tambourine part: stems up/stems down and a circle above certain notes. There is also another common feature in both works: Dance #8 (“Polovtsian Dances”) presents groups of five notes (ten bars after rehearsal “C” and ten bars after rehearsal “F”) and “Rhapsodie Orientale” groups of three (see the second photo below). These odd patterns were written by someone who knew the technique very well and used it with confidence, knowing it could be played without problem. Another thing in common is the presence of a snare drum ostinato (more on this to follow).

“Rhapsodie Orientale” also indicates “+” above the stem up notes (not in the “Polovtsian Dances”, but that´s only a simple notation/edition issue) and “o” below the stem down ones. The notation, its meaning and the technique it entails is obviously the same in both works.

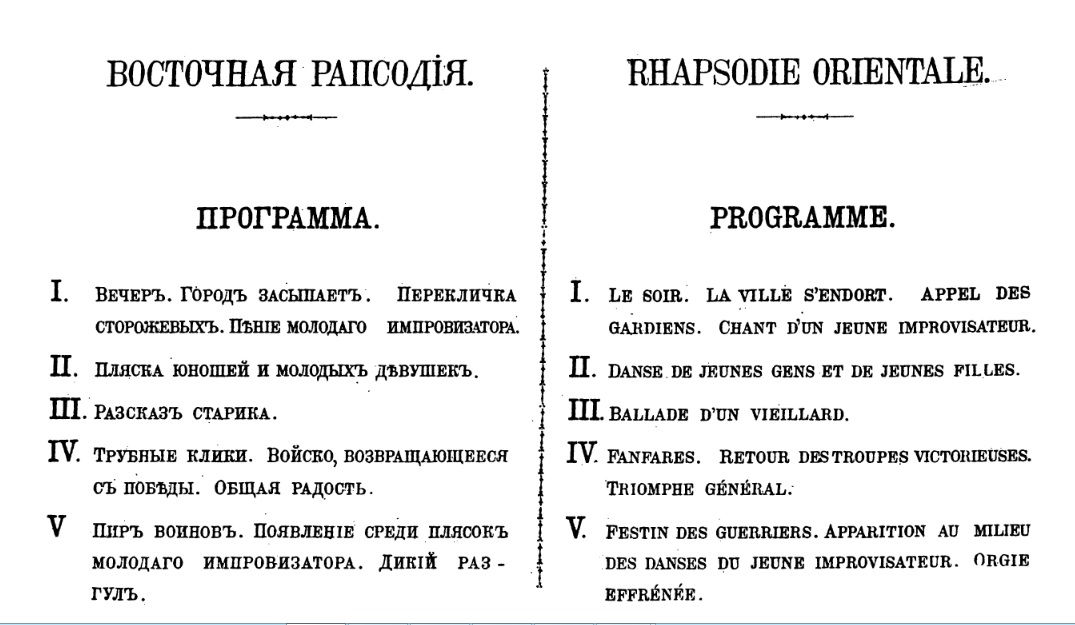

This is the very beginning of II: stems up together with “+” is one kind of stroke, stems down plus “o” is another one. See how once the notation has been stablished in the first two bars, “o” and “+” are not used anymore and the music goes on with no more special symbols:

This is an excerpt from further on in “Rhapsodie Orientale” (it is an ubiquitous pattern during the whole number, as is in Dance #8 from the “Polovtsian Dances”). See that we can find exactly the same rhythm pattern in both works. See also that “o” and “+” are not used anymore because the nomenclature has been stablished in the first two bars. See also the odd groups of three (like the groups of five in #8 of the “Polovtsian Dances”):

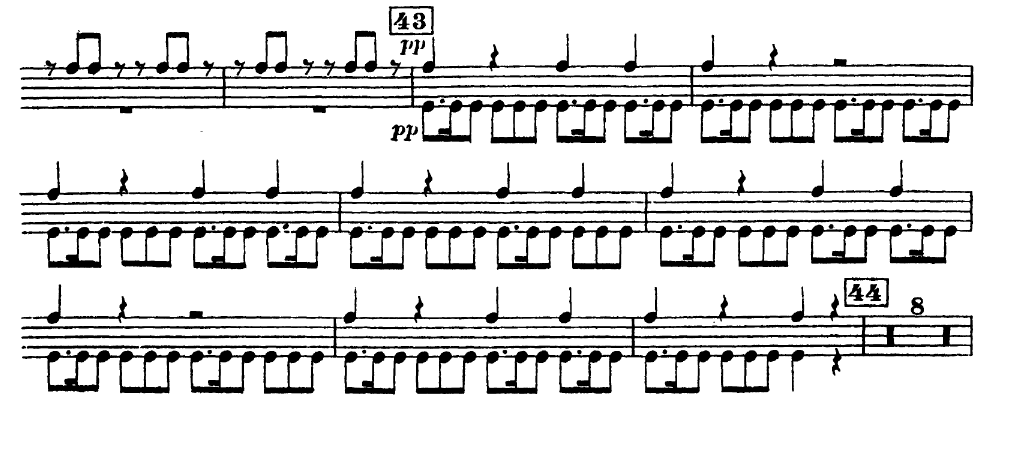

Moreover, we can also find a snare drum ostinato in “Rhapsodie Orientale”, as it happens in the “Polovtsian Dances” (#17). The similarities in the percussion writing in both works are astonishing and cannot be a coincidence (yes, the snare drum patterns are not exactly the same in both works, but you get the idea…):

Borodin wrote just one single tambourine part in his whole life (Symphony #2), never used this particular notation and his tambourine style totally differs from that of the “Polovtsian Dances”. The same happens with Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov who, despite having used the tambourine (specially the latter) with more profusion than Borodin, never used this nomenclature/technique.

Glazunov, by the contrary, wrote many tambourine parts, all of them intricate, rich, lavish and challenging. He also wrote a piece featuring this exact notation for the tambourine (“Rhapsodie Orientale”) and, during the exact same period, he was finishing an incomplete opera by a dead colleague which also features this notation (“Prince Igor”, containing “Polovtsian Dances”). Coincidence? I don´t think so…

It is my humble opinion that, due to the similarity between the tambourine parts of “Rhapsodie Orientale” and the “Polovtsian Dances” (they are almost identical), the notation, the use, the context in both works and the time frame in which they were written, there is no doubt they are by the same person: Alexander Glazunov.

It makes sense to me that, when scoring the tambourine for the “Polovtsian Dances”, Glazunov used the notation and technique he was already familiar with when writing “Rhapsodie Orientale” (or vice versa, as I do not know which work was completed first. Maybe Glazunov worked on both at the same time). So, to me, it is quite clear that the tambourine part in the “Polovtsian Dances” is by Glazunov and not by Borodin, Lyadov or Korsakov. Everything matches perfectly: the technique, the notation, the style and the time frame.

Now that we know who wrote the tambourine part of the “Polovtsian Dances”, it should be easy to know what that nomenclature means and the technique involved. That will be clarified in a future article.

Copyright notice: all the music, parts and scores in this article are in the public domain.

David Valdés started playing piano at the age of seven. He discovered percussion at sixteen and studied both instrumental disciplines for several years but, once he gained his Bmus in Piano, percussion became his main interest.

He got his Bmus in Percussion at the Oviedo Conservatory of Music under Rafael Casanova (OSPA), obtaining the highest marks (“Angel Muñiz Toca” Extraordinary Award and “Final Degree” Award). He also gained a Bmus in Solfege, Sight Reading and Transposition. He also has been trained in Chamber Music, Music Theory and Counterpoint.

David attended the Madrid based “Centro de Estudios Neopercusión”, where he studied with Juanjo Guillem (ONE), Enric Llopis (ORTVE), Francisco Diaz (OST), Juanjo Rubio (OCM), Oscar Benet (OCM), Belen López, David Mayoral and Serguei Sapricheff.

David studied at The Royal Academy of Music in London with Andrew Barclay (LPO), Simon Carrington (LPO), Leigh Howard Stevens, Nicholas Cole (RPO), Dave Hassell, Paul Clarvis, Neil Percy (LSO) and Kurt Hans Goedicke (LSO), where he gained his Postgraduate Diploma in Performance (Timpani and Percussion) and his LRAM. He also studied Jazz with Trevor Tompkins, Orchestral Conducting with Denise Ham and Choral Conducting with Patrick Russill.

David has attended many courses and master classes by renowned musicians: Jeff Prentice, Rainer Seegers, Benoit Cambrelaing, David Searcy, Ben Hoffnung, Philippe Spiecer, Enmanuel Sejourné, Keiko Abe, Eric Sammut, She-e Wu, Joe Locke, Anthony Kerr, Dave Jackson, Makoto Aruga, Chris Lamb, Collin Curie, Evelyn Glennie, Mircea Anderleanu, Steven Shick, John Bergamo, Airto Moreira, Birger Sulsbruck, Peter Erskine, Dave Weckl, Bill Cobham, Carlos Carli, George Hurst, Arturo Tamayo, Collin Meters, José María Benavente, Román Alís, Fernando Puchol, Michel Martín, Javier Cámara, Francisco José Cuadrado… These musicians have trained him in Percussion, Piano, Contemporary and Modal Harmony, Jazz, Conducting, Music Production, Editing and Microphone Techniques.

He was awarded the “Principality of Asturias Government Scholarship” three times in a row, he was finalist at the “International Keyboard Percussion Competition” sponsored by the “Yamaha Foundation of Europe” and was runner-up for the “Deutsche Bank Pyramid Awards”, given to innovative performance and composition projects.

David has played with the following orchestras: Gijón Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Principality of Asturias Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Oviedo Filarmonía (Spain), Asturias Classical Orchestra (Spain), Spanish National Orchestra (Spain), Catalonian Chamber Orchestra (Spain), Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Orchestra of the University of Oviedo (Spain), City of Avilés Symphony Orchestra (Spain), Moscow Virtuosi (Russia), Concerto München Sinfonieorchester (Germany), WDR Rundfunkorchester Köln (Germany), Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic Orchestra (Poland), Orquestra do Norte (Portugal) and the Ulster Orchestra (UK). He has also played with early music ensembles (Forma Antiqva, Memoria de los Sentidos, Sphera Antiqva and Ensemble Matheus), and chamber groups (RAM Percussion Group, Neopercusión and Ars Mundi Ensemble).

David has translated into Spanish “Method of Movement for Marimba” (L. H. Stevens), the internationally acclaimed book used in conservatoires and universities worldwide. He is, also, the Spanish translator of www.percorch.com, website used by many orchestras to organize their percussion sections.

He has taught at the Gijón and Oviedo Conservatories of Music. His discography includes many different genres, and he has worked as a session musician, arranger and on-line instrumentalist as the result of his interest in recording, sound and technology. David is a busy timpani/percussion freelancer and runs his own business: “Producciones Kapellmaister”.

David Valdés enjoys sailing, windsurfing, snowboarding, rollerblading, reading, and playing with his two daugthers: Carmen and María.

Thank you, Mr. Valdés, for your research!

History alwasy fascinates me, and even though I had a teacher that gave us an input on the performance of this tambourine part (he heard it from a Russian percussionist), I never knew anything about how the part was written.

Looking forward for Par 2!

Gracias!

No conocía estos datos, y fue muy enriquecedor.

Espero el siguiente!

Hi David:

Absolutely wonderful historical insights and information.

I did come across some brief interviews and quotes of Borodin, and there was a reference for his fondness of the “cuckoo,” and using it in scores. Is there a possibility that the “o” above the tambourine part on the eighth note could be the second syllable of “cuckoo?” I know this is a stretch, and the inverse, but… do you think this might be plausible?

Again, thank you for sharing your wealth of information.

It is doubtful that the “o” refers to the sound a “cuckoo” makes.