by David Valdés

“The Nutcracker” is a work that, despite being part of the repertoire and being performed/played very often (specially during Christmas), it is played with some mistakes due to a wrong interpretation of the instructions given by Tchaikovsky and the writing that he used. This mistakes are so embedded (they are almost tradition!!) that it is almost impossible to find a “correct” version of this masterwork.

It is in the tambourine part that we can find problems (but also in the triangle part) and, for that reason, it is that I am writing about the “Danse Arabe” (included in the suite. It is “Le café” in the ballet).

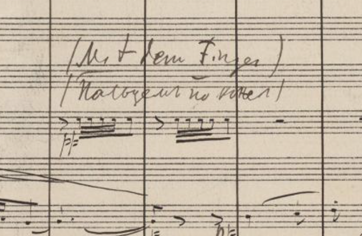

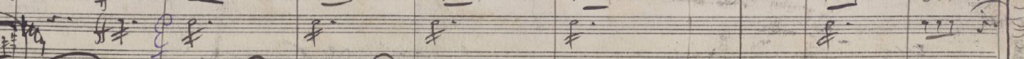

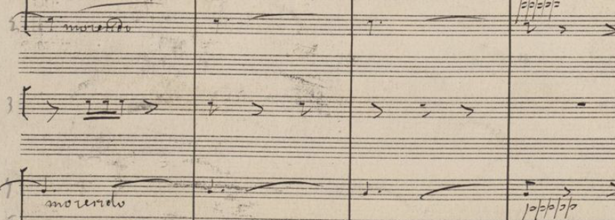

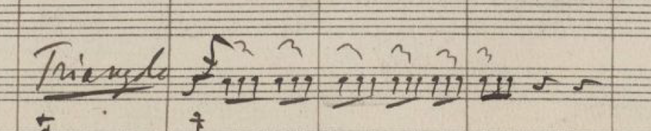

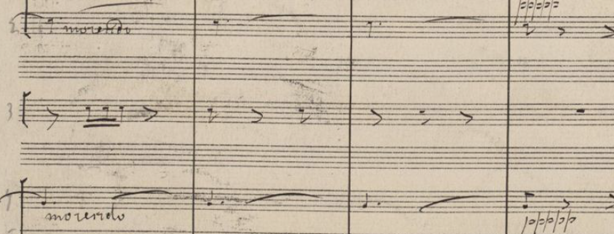

Tchaikovsky wrote this very clear instructions in the manuscript:

He used four 32nd-notes and an 8th-note on the third part. The instructions in the upper line reads (in German “Mit dem Finger” (with the finger). The bottom line reads in Russian “Palzem po koze” (with the finger along the skin). See that the old saying “traduttore, tradittore” is true (“translator, traitor”), as the indication in Russian contains more information than the one in German.

The “problem” is that percussionists play that rhythm literally, but the indications by the composer (specially the one in Russian) are a very clear clue that entails a finger roll.

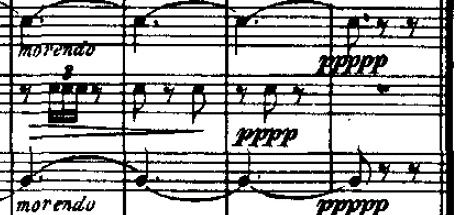

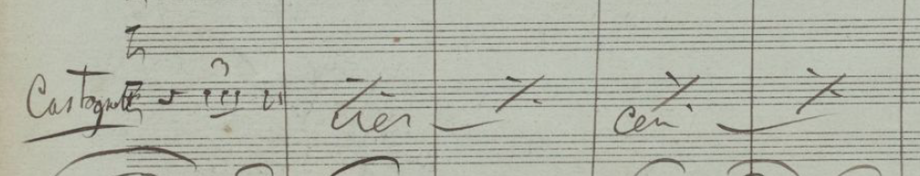

We can find the following indications in the first edition of the ballet:

The upper line (in Russian, using Cyrillic alphabet) reads “Palzem po koze” “with the finger along the skin”). The bottom line (in German) reads “Mit dem Daumen” (“with the thumb”). Anatomically speaking, we have a more generic indication in Russian (“finger”) and a more specific one in German (“thumb”). But, the indication in Russian is much more specific in terms of technique: “po koze”, (along the skin). That points very clearly to a finger roll.

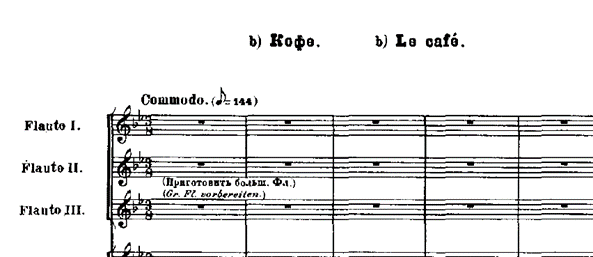

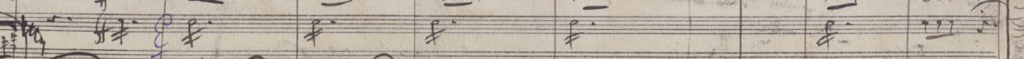

We can find the following instructions in the suite:

The upper line (in Russian, using Cyrilllic alphabet) reads “Bolshim parchem po koze” (“Thumb along the skin”). The bottom line (in German) reads “Mit dem Daumen” (“with the thumb”). Now, both indications are anatomically consistent (thumb), but the Russian version is the one containing technical information (as in the ballet and in the manuscript): “po koze” (“along the skin”). This, very obviously, suggests gliding on the head, which entails a finger/thumb roll.

Obviously, playing articulate, discrete notes using the thumb makes no sense at all. The indications to use the finger/thumb are a clear reference to a roll, which is reinforced by the Russian instructions “along the skin” (missing in German).

All of the tambourine passages are solo (we are not doubling any other instrument, we are just a “color”) and, for this reason it is not very important if we play a roll or four 32nd-notes, as we do not clash with any other instrument or thematic material. This, maybe, has contributed to perpetuate the mistake, as “anything sounds good”.

Literality has made that almost every percussionist in the world (Russians included!!) plays this dance articulating each note, when Tchaikovsky clearly indicated a finger roll.

This reinforces what I always say (and will never get tired of saying); namely, that we are INTERPRETERS and not mere readers. Reading as a solicitor would do makes no musical sense (even les if we read not having read the instructions given or not having made the effort to translate them). As INTERPRETERS we have to go further than the 32nd-notres that Tchaikovsky wrote (he wrote that way because there was no standard at that time. There is no standard even today!!!), understand the given instructions, connect the dots and go beyond mere literality. To interpret, and not to merely read, is what makes us better musicians, great performers and not reading/writing software like Sibelius or Finale (a computer will always “read” way better that us, so let´s not compete in reading but in interpretation).

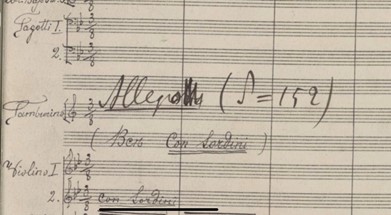

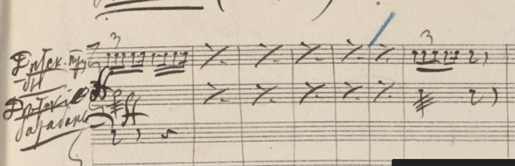

There are other clues that point in the direction of a finger/thumb roll. The tempo indication in the manuscript is Allegro ♪=152 (maybe 159. That last number is not very clear but, whatever number it is, it is still a very fast tempo):

See that the original indication was “Allegretto”, that Tchaikovsky crossed out “-tto” and that he modified the “e” to convert it into an “o”. He initially wanted “Allegretto”, but modified it to a faster “Allegro”.

The tempo indication in the first edition of the ballet is Commodo ♪=144. A slower tempo than in the manuscript (just slightly). Maybe Tchaikovsky had a thought about it and got back to the original “Allegretto” that he crossed out in the manuscript. Still a fast tempo.

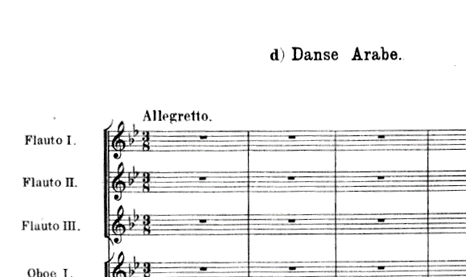

The tempo in the suite is, simply, Allegretto, without metronomic indication (remember that the Allegretto in the manuscript was ♪=152, a very fast pace):

The suite goes back to the original crossed out Allegretto, but remember that Tchaikovsky´s metronomic indications are very precise: 152 and 144. Both are very fast tempi (very far from the agonizing and pesante versions that seem to be the norm today), and those tempi determine what technique is to be used. Playing articulate and discrete 32nd-notes at the tempi indicated is hard and not very practical. The tempi suggest, because of the high speed, a roll.

These two reasons (the clear instructions in Russian by Tchaikovsky and the tempi indicated) point to a finger/thumb roll. Lacking a writing standard, he used 32nd-notes. But there is one more reason that proves that Tchaikovsky was thinking about a finger/thumb roll, and that is that he used two different writings for the two different types of roll on the tambourine.

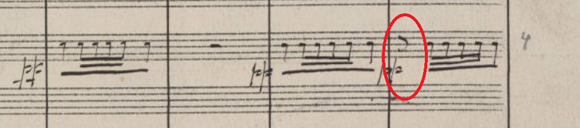

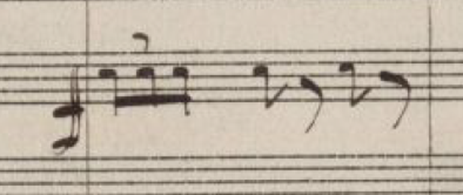

“Danse Arabe” is the only number in “The Nutcracker” which uses a finger/thumb roll. He clearly indicated that technique using written instructions (as we have demonstrated above), but he had to use (to the eyes of a contemporary percussionist) a strange notation, as there was no standard at that time (still there is not today). That he wanted a finger/thumb roll is very clear when we compare the writing he used to indicate a shake roll. Here we have the ending of No. 3 (“Petit Galop”), where he uses slashes to indicate a shake roll (again, please do not be literal and tell me that that means 16th-notes, as no other instrument plays them -so we are not doubling- and the galop is a dance of popular, country origin, so a roll is in its character).

He also uses slashes at the end of the “Trepak”.

Why is it that no one gets literal at the end of the “Trepak” (playing 32nd-notes), but some do get literal in the “Little Galop” and play 16th-notes? The point is that Tchaikovsky uses two different notations for two different rolls; namely, slashes for the shake roll and discrete 32nd-notes for the finger/thumb roll (the latter accompanied with written instructions in Russian and in German). Why did Tchaikovsky wrote the finger/thumb roll in that way? Because there was no writing standard and that time. Easy.

There are still a couple of issues with this dance:

- On the fifth-to-last bar we can find a discrepancy in the suite when compared to the manuscript and the ballet.

The manuscript shows an 8th-note rest on the first part of the bar.

The first edition of the ballet also features that rest:

It is in the first edition of the suite that the rest is substituted with an 8th-note:

My opinion is that, because the manuscript and the first edition of the ballet are consistent, the presence of that 8th-note in the suite is a mistake by the copyist/editor. I also find a musical explanation for the rest to be the correct option: the texture gets lighter and lighter and Tchaikovsky “takes notes out” as we approach the end of the dance. It is quite musical not to repeat two identical bars and to have “less density” of notes as we get to the end, thus creating a feeling of ritardando by “rhythmical elimination”.

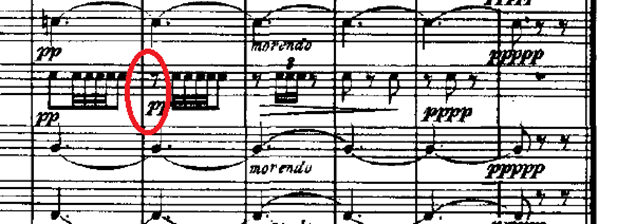

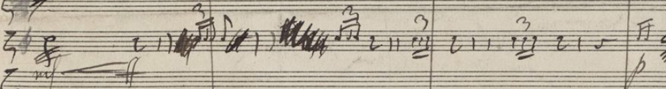

- The fourth-to-last bar features two 32nd-notes and one 16th-note in the manuscript:

This writing is consistent with several elements in the dance: 1) 32nd-notes to indicate a roll. 2) It doubles (embellished) the ostinato accompaniment in the celli. 3) It lightens the texture, as I explained above, as we get to the end.

But, that bar features a triplet in the ballet and in the suite:

There is NOT a single triplet in the whole Danse Arabe. Why would Tchaikovsky write non-thematic material just one single time in the form of a triplet? He didn´t write any triplet; he wrote two 32nd-notes and one 16th-note, but the length of the upper beam (slightly longer, but not reaching to the next figure) confused the engraver/editor and converted the original rhythm into a triplet.

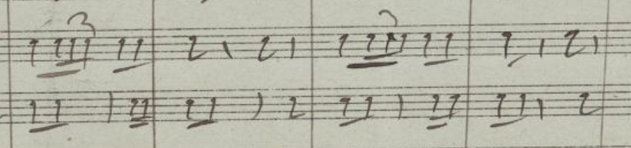

Had Tchaikovsky wanted a triplet, he would have written it, like he did in the toy trumpet part in No. 5 (“The Grandfather Dance”),

the toy drum part in No. 7 (“Scene”),

the triangle part in No. 9 (“Dance of the Snow Flakes”),

the castanets in No. 12a (“Spanish Dance”-“Chocolat”),

the triangle part in No. 12f (“La mère Gigogne”),

and the triangle part in No. 13 (“Waltz of the Flowers”).

So, Tchaikovsky wrote the “3” in his triplets every single time. He did not write it in the fourth-to -last bar in the “Danse Arabe”, so that is clearly not a triplet but two 32nd-notes and one 16th-note, which have to be interpreted as the previous 32nd-notes, as a thumb roll, but this time shorter, taking the rhythmic space of just one 16th-note, ending in the fourth 16th-note of the bar (the “rhythmical shortening” I mentioned above).

I know that, after many, many years of playing the “Danse Arabe” using articulate 32nd-notes, this article can be felt like me hitting a wasps nest with a bat, but proofs and facts are there. Do not blame the messenger!!!

In order to make musical decisions, we have to be as informed as possible. Now we have one more option. Does this mean that we have to play this dance using a finger/thumb roll? Not necessarily. Make beautiful sounds and good music, as those are the important things.

I, for instance, have played this part in a variety of ways; articulate 32nd-notes and finger rolling (both on tambourine), but I have also played, using a riq, 32nd-notes hitting the jingles while holding the riq “soft cabaret style”, as if I was playing accompanying a beautiful veiled-dancer in the Sultan´s palace. Using that Oriental approach, I have even played a quintuplet instead of four 32nd-notes (both on tambourine and on riq), as that is the rhythmic motive played by the woodwinds.

Do music, but do it making informed decisions.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT DAVID

I was playing in a production of The Nutcracker around the same time I saw this idea posted. I had already questioned the notation, but for the first rehearsal I played it as notated and something seemed off. For the next rehearsal I switched to finger rolls, and it filled in the score better and made more musical sense to me. After the production was over, I heard several compliments about this movement and how I played it.

Scanning through 2 different 1890s method books in my collection. I can’t find mention of a thumb roll technique anywhere. I believe the Russian instruction merely says where to stroke your finger. On the skin, not on the wooden rim.

Dear Nick.

The indication is clear: “Palzem po koze”. That literally translates as “with the finger along the skin”, where the key is “along the skin”, entailing a finger roll.

Finger rolls have been used for milennia, as they are a technique inherent to tambourine playing. I own (and also re-edited) a bunch of tambourine methods from the early 19th-century and they describe different finger rolls with precision (even an infinite finger roll!).

I know that playing this dance using a roll after decades and decades of playing it “wrong” may seem bizare, as we are now used to that “incorrect” interpretation, but musical and common sense (and also the manuscript!) tell us the truth.

Best regards.